I discovered PWR BTTM only a month ago, and they probably wouldn’t have crossed my radar without a little stoking from Apple Music. One Friday in early May, a raw punk thrasher called “Big Beautiful Day” from their new release “Pageant” found its way onto my New Music playlist. I was immediately enamored. As I began to read about their image of queer advocacy, the hook sunk deeper. Here were a pair of gender non-conforming musicians rocking drag, while howling out songs about bodily autonomy. I dug it in a big way, especially since the DIY punk scene I’m fluent in is built on the back of white privilege and hypocrisy.

I immediately set out to tell all my friends about them. These were artists I considered important. I wanted their music, image, and message to reach as many people as possible.

Then, something bizarre happened. I typed their name into the search bar of my iPhone and nothing populated the screen except the spinning march of the loading wheel. Even the songs I had downloaded became a dull, unplayable grey. A quick look at Spotify revealed the same. PWR BTTM had all but disappeared from the Internet. Total erasure.

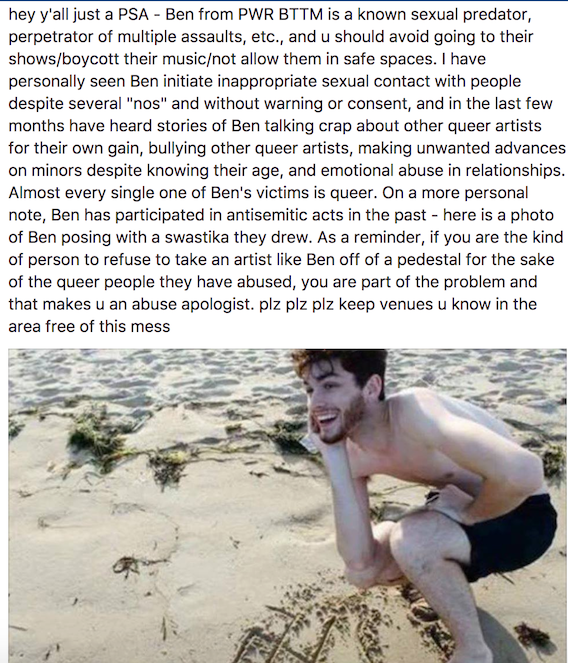

What happened is so well-documented and discussed that I fear sounding like a broken record to cover it again. But for those of you who steer clear of music news or queer politics, it began with a post from Facebook user named Kitty Cordero-Kolin on May 11th. In it, they outlined lead singer Ben Hopkins’ history of sexual assault and predatory behavior toward fans of the band. This was followed by an anonymous report in Jezebel from a person allegedly raped by Hopkins, who had initially thought they seemed “like an okay person… because of what they preached.”

Screenshot of Cordero-Kolin’s Facebook post via Jezebel

In response, PWR BTTM released the following statement on Twitter trying to mitigate the fall-out:

— PWR BTTM (@PWRBTTMBAND) May 11, 2017

But it was no use. The axe came swiftly, suddenly, and with a finality that I haven’t before seen in the music industry. Both the band’s management company, Salty Artist Management, and their label, Polyvinyl Records, severed ties with them immediately and their music was ripped from the interwebs. Supporting acts and touring musicians dropped from their tour, which itself collapsed like a matchstick house under a wrecking ball. This could be the end for the once lauded and promising queercore duo.

And you know what? Good.

The decisiveness with which the queer community and Polyvinyl excised PWR BTTM is a victory for victim advocacy. No matter how much I and others like me enjoyed their music, the lives of those harmed by people like Hopkins take precedence.

But hold on, you say. How do we know that these allegations hold water? What if the lives and careers of these young musicians were ruined by faulty claims?

Though the purpose of this piece isn’t to chronicle the clanking gears of rape culture, here’s a little taste for those quick to come to PWR BTTM’s defense. Consider that sexual assault is one of only crimes met with immediate suspicion of the victim. If not written off by police, victims face numerous obstacles between report and conviction. Whether it’s interrogatory information gathering by police, failure of the DA’s office to bring a case to trial, or slandering by the friends, family, and community of the accused, victims march through an abusive gauntlet. Even if they manage to take it all the way to the finish line, only 18.4% of reported rapes lead to an arrest and 2.3% lead to conviction. To emphasize, those are only reported rapes. Those numbers almost disappear when considering that seven out of ten go unreported altogether. It’s no wonder that victims often discourage one another from contacting authorities at all.

The NSVRC reports that false rape statistics are often overinflated, falling somewhere between 2% and 8% in reality. Without pointing immediate blame at Hopkins, the experience of the alleged victim should be taken at face value. Entering a sexual assault case by believing the victim is the best way to rightly ascertain the fact of the matter. Polyvinyl acted as an ally by swooping to the aid of someone who would most likely be sidelined by the system.

“I mean, you’ve let someone in your car before, right? You’re known for giving people lifts. You’re sending mixed messages, that’s all I’m saying.”

To quote The Atlantic, “If there was ever a case of art and artist being inseparable, this is it.” It’s the antithesis to the ongoing debate of whether one can sit down to watch Annie Hall knowing full well that Woody Allen probably raped his stepdaughter. It’s a glimpse at what the world might look like if people cared more about Rihanna’s bruised face than getting the latest Chris Brown dumpster-liner. It’s what could have saved over forty women a roofie and a nightmare at the hands of Bill Cosby. As we know though, it’s not.

If this debacle with PWR BTTM has taught me anything, it’s that the entertainment industry has its priorities, and they’re usually at the expense of the most vulnerable among us. Hopkins and bandmate Liv Bruce rose to prominence as queer-community inspirers, donning cloaks of lost souls overcoming disempowerment. Before “Big Beautiful Day” was taken down, I found its message of self-affirmation through gender expression gloriously refreshing, but it sours when knowing that Hopkins might be a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Had they been a bit more famous, these allegations would probably have gone unheeded, and more victims may have piled up.

Abusers, especially powerful ones with tremendous earning power, are protected by the pockets they line. College football stars rape with impunity so long as they win games. R. Kelly and Cee Lo Green still have careers despite well-documented histories of abuse and assault. Woody Allen still releases a movie every goddamn year.

The queer community claims this is because of the pedestal cishet stars are placed on, but I think the difference is a little simpler than that. The more that an artist brings to the table financially, the more music labels, movie studios, and other industry cogs have invested in keeping them producing. PWR BTTM may have been critical darlings, but the fiscal void they leave is far smaller than one that someone like Beyoncé would create with her absence. Money talks, and that bottom line is much sweeter than the handful of lives that predators trample on their way to the top. It’s a sick sort of hypocrisy.

We can wring a bit of solace out of the injustice though. The extinguishing of PWR BTTM proves that companies are capable of acting on behalf of victims, even if it’s against their own (admittedly short term) interest. It also illuminates just how skewed our priorities are when it comes to dealing with celebrity assault accusations. If we treat people like they are invincible just because “they’re famous,” they are going to act like it. Public figures aren’t automatically paragons of good because we pay attention to them.

More than that, we need to start caring when these allegations are brought and demanding the kind of decisive action we saw in the PWR BTTM case. If we make the statement that these kinds of actions are unacceptable from anyone, maybe they will start disappearing. Maybe we won’t even elect people that are known abusers.

What do you think? Does the entertainment industry need more accountability in dealing with sexual assault? Let us know in the comments.

Tags : Apple Music, Ben Hopkins, buzzworthy, Celebrities, featured, Internet, Jezebel, lgbtq, music, Polyvinyl, Punk, Punk rock, pwr bttm, queer, rape culture, scandal, sexual assault, Spotify, streaming, The Scene, twitter

Subscribe. Follow. Like.

To RSS Feed

Followers

Fans